There is an important distinction between impactful and improvement that often gets blurred with regards to Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns, to which this first issue of Dark Knight III: The Master Race serves as a sequel, building on three decades of nostalgia for the original. The Dark Knight Returns’ impact is a matter of unquestionable fact; alongside Moore’s Watchmen it marks the genesis of the Dark Age of Comics, an era which conflated adolescent angst and aggression with maturity, as if making art less accessible to children made it less childish. All of the major moments in the industry during this period, from Carnage, Bane, and Doomsday in the mainstream to the initial tenor of Image and Vertigo at the fringe, were in part responses to and replications of Dark Knight’s dark direction. In the very years that Giuliani was sanitizing and disneyfying the Times Square of the real world, comics were obsessively adding new layers of grit, grime, and crime to those same city streets.

The Dark Knight Returns’ impact on the character of Batman specifically was further reaching still. Tim Burton’s gothic gargoyle, Bruce Timm’s noir ninja, and Christopher Nolan’s rightwing security hawk all owe it a direct debt. So much so, indeed, that the popular narrative of the character has become that Batman was not really Batman till his reinvention at the hands of Miller; that the violent vigilante birthed by Bill Finger and Bob Kane had been for forty years forgotten, secretly Stepford-ized by the “High Camp Crusader” best embodied by Adam West.

That Millar’s Dark Knight was an improvement over West’s Caped Crusader was regarded as an unquestioned fact for decades. It’s only been in recent years that Miller’s seminal miniseries has begun to show its age, with fans questioning its continued relevance; re-reading it and Watchman, the later holds up far better than the former.

At the same time, with the release of the ‘60s television show on Blu-Ray and Jeff Parker’s acclaimed digital first comic, Batman ’66, fans have grown more accepting and appreciative of the character’s ability to adapt to satirical and somber stories alike, fluidly transitioning between the two without ever losing the essential but elusive je ne sais quoi of Batman. Having recently re-watched the series, it does not try and fail at being a serious take on Batman; it tries and succeeds at being a comedic approach to the character, and as a result has only gotten better since the lazy summer mornings as a kid when I watched the syndicated reruns ad nauseam.

The Master Race is Miller’s return to a well run dry. In the ‘80s, Miller’s sadist, sociopathic Batman was utterly novel, a refreshing respite from the saccharine sap imposed by Wertham and the Comics Code Authority. Since that time there’ve been equally mature interpretations of the character, albeit more nuanced and three dimensional, as per Loeb, Morrison, and Snyder’s work on the character. Simply pitting Batman against the police and bloodying his gloves is no longer an interesting angle.

Even Miller’s previous follow-up, All-Star Batman and Robin, the Boy Wonder, was a logical progression of the direction Returns had taken, turning every character into a caricature and allowing absurdity to unfold. Just as Superman in Returns was a government stooge, in All-Star Wonder Woman was a bra burning militant feminist and Hal Jordan dumb-as-a-doorknob, easily dispatched by yellow paint, a pitcher of lemonade, and a preteen in pixie-shorts. Unlike the by-the-numbers Master Race, “the goddamn Batman” was goddamn fun to read.

Furthermore, Returns success was in large part due to its scathing critique of then contemporary ‘80s American culture. The opening panels of The Master Race halfheartedly swing at social relevance, depicting white cops taking aim at a fleeing black youth in a scene evocative of Ferguson and similar incidents, but absent of any social commentary such serves no purpose other than to ground the story in the present day, racial tensions and all. The same feels true of the accompanying text messages, as if Miller felt he needed a modern equivalent to the talking head pundits featured prominently throughout Returns.

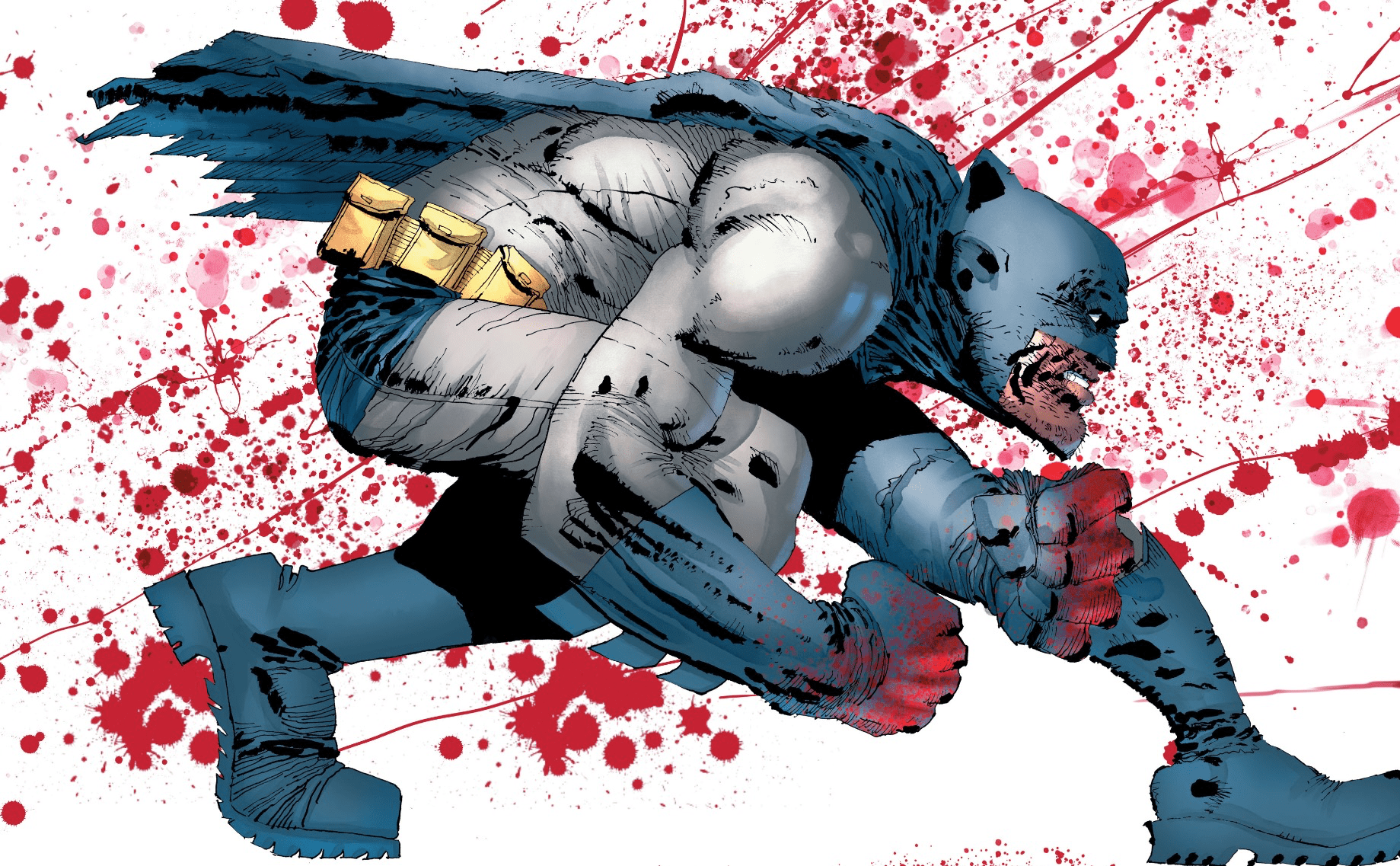

Not only is the story too self-serious for too shallow an interpretation (even accounting for the revelation on the last page), the art suffers just as much. On Returns and Strikes Again, Miller’s own art, though never beautiful, was at least bold and kinetic. On All-Star, Lee’s pencils surpassed even his own work on Hush, and would have even redeemed Miller’s story had it truly been as bad as internet commentators would have you believe (I for one am staunch in my defense of it). Andy Kubert is certainly capable of illustrating Batman; his work alongside Morrison on Batman and Son and later arcs definitively proves as much. But here, in channeling Frank Miller, neither Kubert’s own strengths as an artist nor Miller’s come through on the page.

Just as Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns saw an elderly Bruce Wayne, long past his prime, coming out of semi-retirement, The Master Race sees Miller himself do the same. Unlike Wayne, Miller’s clearly lost a step or two, no longer in fighting form. Despite the modern setting, it’s take on Gotham is stale and outdated. Far from the masterpiece which The Dark Knight Returns is remembered as, the first issue of The Master Race is only a masterful failure.

2.0/10