Man of Steel

Superman and Batman have both been mainstays of American popular culture for over seventy years now, but in that time great differences have emerged, not only in their characteristics, but even in the manner in which they are characterized.

Batman has a number of well-defined attributes; he is a billionaire with exclusive weapons technology, an expert in all styles of armed and unarmed combat, the world’s greatest detective, and a student of the world’s great yogis and sages. Different writers emphasize these attributes in various degrees, but contrasting characteristics are never introduced. Grant Morrison’s more cerebral Caped Crusader remains an affluent ninja vigilante, while Frank Miller’s psychopathic and sadistic Dark Knight retains his forensic expertise and spiritual training.

Not so with Superman. In the hands of different writers vastly different and even competing characterizations are put forth. The basic elements of the Superman mythos (the orphaned alien, the duel identity, etc.) may be identical across a number of stories, but their depiction of the central protagonist is often contradictory.

In the characterization of Superman there exist a number of dichotomous attributes. These go beyond the question of whether the Clark or Superman persona is the true identity, though the answer to such a question will inevitably be dependent on which side a writer accepts and which he rejects in regards to said dichotomies. Arguably the most important dichotomy is in regards to Superman’s divinity or humanity, which I refer to as Super-God vs. Super-Human. To be clear, I am not contending that he is written literally and explicitly as a god or messiah, with “god” corresponding to a certain back-story or power-level, but rather that the function he serves in the story is thematically similar to God or a god.

The Super-god viewpoint can take on several manifestations. Of these, the least contentious is the depiction of Superman as fulfilling the role of a pagan deity, with the Justice League as an Olympian pantheon of sorts. In such a view the great stories of comics and cinema serve the same imaginative role in American culture as the myths of gods and heroes did in pagan mythologies, sans the religious reverence.

Grant Morrison, in taking this viewpoint to its logical conclusion, identifies Superman as a “Sun-god from Smallville” and in his magnum opus All-Star Superman makes this literally the case: after completing twelve heroic labors, one of which being the implied creation of the “real” universe of we the readers, Superman transfigures into pure light, ascends to the heavens, and makes his dwelling in the Sun until his promised return. He is in this way Ra, Apollo, and, most obviously, Christ (but more on that in a minute).

While the pagan view is applicable for most superheroes (though more so for DC’s characters than Marvel’s), the monotheistic viewpoint is more unique to Superman. This was the understanding articulated by Bill Jemas in an early issue of Marville, in which he stated something to the effect that all good Superman stories answer the question of how a loving God could exist alongside and interact with human beings.

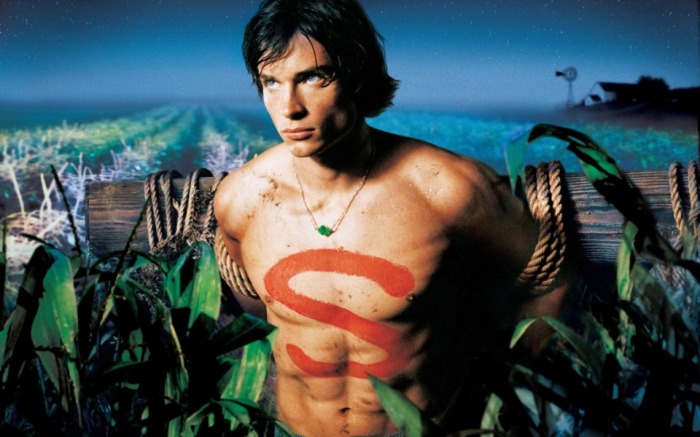

The third and most prolific variation of the Superman as god/God theme is the Christological view. This is an oddity, to be sure, given the character’s Jewish creators, but it remains a prominent and recurring theme nevertheless. To my knowledge 1978’s Superman: The Movie was the first instance in which the Christ motif was consciously implemented, with 2005’s Superman Returns reaffirming the connection. While countless more examples can be given, one needs look no further than the promotional poster for the first season of Smallville in which Clark is hung upon a scarecrow’s stake in an image intended to evoke the Crucifixion.

Smallville

However, not all Superman tales which reference the Christ story come down on the side of Superman’s divinity. Superman’s chastisement of worshipers following his death and subsequent resurrection made it clear that the editorial staff at the time had no interest in drawing parallels to Christ’s own rising from the grave. Furthermore, Mark Waid’s Kingdom Come about the “Second Coming of Superman” deliberately utilized Christian apocalyptic literature and imagery, even going so far as to make a Protestant minister its point of view character, in order to later underscore Superman’s rejection of such status and reaffirmation of his humanity.

The classic example favoring the Super-Human position is Alan Moore’s timeless “Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow?” in which a happily de-powered Superman, now using the alias Jordan Elliot (in honor of Jor-El) speaks critically of his former identity, saying the Superman didn’t think the world could get along without him.

The most typical indicator of a writer’s position in the debate is whether Superman is portrayed with absolute moral certainty or as flawed and conflicted. Christopher Reeves’ portrayal is of a man never in doubt of the rightness of his actions. Grant Morrison goes further. In his Superman such moral certainty makes victory always certain as well. This comes from Morrison’s near-religious veneration of Superman, calling him the greatest idea humanity has ever had, in that he is a perfect individual who can overcome all evil. This is most clearly seen in Morrison’s Final Crisis, in which Superman is able defeat evil-incarnate with a single word and restore all of existence by the light that is in him. Even actions said to be metaphysically impossible are accomplished simply on the basis that he’s Superman.

Waid’s Superman, in contrast, finds that every decision he made throughout the majority of Kingdom Come was wrong. Likewise Brian Azzarello, in the recent classic For Tomorrow, is portrayed as lost and alienated in the absence of Lois from his life. While Waid’s Superman walked on water, only later to be revealed as sacrilege, Azzarello’s specifically refuses to do so in the presence of a priest in a conscious rejection of the Christ connection.

One final point deserves mentioning. By all expectations the duel identity ought to be more utilized by proponents of the Super-God position, particularly in reference to the doctrine of Christ being one Person but having two Natures (being fully God and fully Man), but this seems not yet to be the case. There is a painting by Alex Ross (himself the son of a minister) of Clark Kent ripping apart his shirt to reveal the “S” insignia underneath which almost forces the viewer to contemplate the Transfiguration, but otherwise no stories come to mind in which the character is “fully Clark and fully Superman.” One is always a mask for the other.

Dawn of Justice

Pingback: The Secret of Superman’s Identity | The Hub City Review

Pingback: Superman: American Alien #5 | The Hub City Review

Pingback: Superman: American Alien #5 | The Hub City Review

Pingback: Batman V Superman: Dawn of Justice | The Hub City Review

Pingback: Immigration and Assimilation in the Superman Franchise | The Hub City Review

Pingback: Turning ideological history into personal history through Superheros | summer2016creativewriting

Pingback: Action Comics #960 | The Hub City Review

Pingback: Action Comics #964 | The Hub City Review

Pingback: Black Liberation Theology in Marvel’s Luke Cage | The Hub City Review

Pingback: Action Comics #972 | The Hub City Review

Pingback: NYCC Friday: ComiXology, Theology, Some Booze, and a Bit of Poison… | The Hub City Review

Pingback: The Real Blaspheme of Mark Russell’s “Second Coming” | The Hub City Review