There’s a deep and lasting irony to Jimmy Olsen’s moniker of ‘Superman’s Pal’. On the one hand there’s no doubt as to the genuine connection and friendship between the Man of Steel and the Daily Planet’s cub photographer. Jimmy and Superman share much of the same friend group, and even there, it’s clear that Jimmy is in Superman’s inner circle, evidenced by the unique signal watch given to him alone by Superman; few others in the world have such direct access to the Sun-god from Smallville. And yet on the other hand, Jimmy has no idea as to Superman’s secret identity. This is not merely one friend having a personal secret that he’s not ready to share with another. Superman’s secret identity is the very core of who he is – an all-powerful being who does not revel in lording that power over us, but rather daily choses to humble himself and take on the hardships and indignities of living as a human himself. Without understanding that, Jimmy can never truly understand his friend Superman. And likewise for Superman’s pal Jimmy Gunn.

It’s clear from his new Superman film that James Gunn understands Superman’s universe and supporting cast (for the most part). Metropolis and its environs are shot in hyper-saturated hues reminiscent of the vibrant art seen in the four color comics of the Silver Age. Far from being merely New York and its skyline, replete with the Statue of Liberty and Twin Towers, as in the Donner films, Gunn’s skyline is classic Art Deco meets City of Tomorrow. Between the buildings are not ‘70s era muggers, but rather killer kaiju and hyperdimensional imps. Luther’s million monkeys typing away at keyboards might make no sense in a world with bots and algorithms that could easily do the same, but it’s a more interesting way of visualizing a modern social media troll farm, befitting of the cinematic medium. This is not “the world outside your window”; it’s the world of DC Comics come to life.

Where the same approach does not work is in human beings doing everyday human things with the same absurd stylization. The Boravian invasion of Jarhanpur – with Western-armed infantry marching on foot alongside tanks, while waiting for them directly across the border is vaguely ethnic third-world villagers armed with sticks and stones – is a fanciful fever-dream of what modern warfare looks like. Against the strangeness of flying folk with capes and wings and magic rings should be juxtaposed ordinary people behaving as they realistically would, but instead Gunn portrays a battle closer to the one on Endor than any here on Earth.

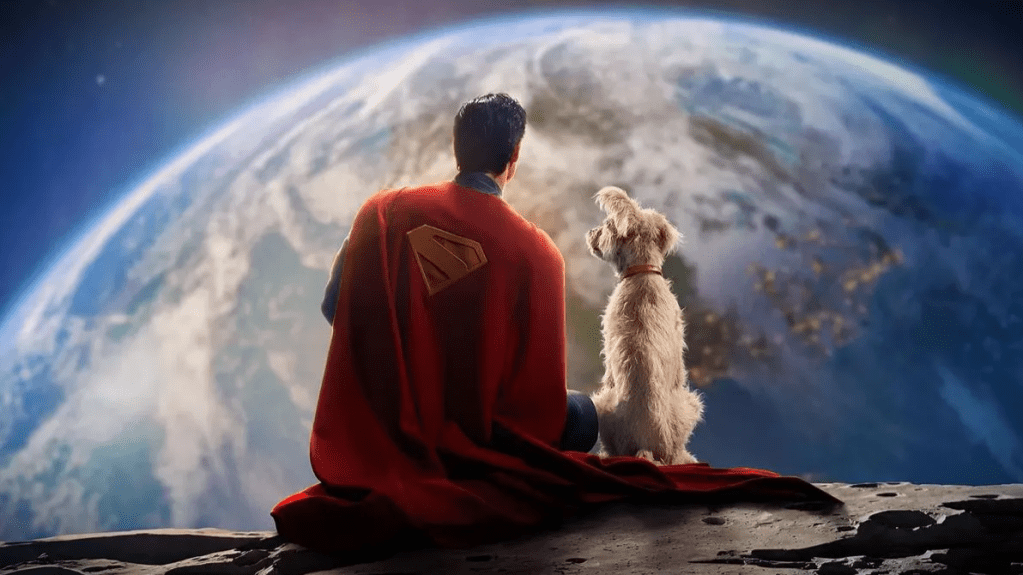

Carrying Superman – dragging the character literally, in the opening minutes of the film, and figuratively the film itself throughout its runtime – is Krypto the Superdog. After his signature soundtracks (which this film uncharacteristically fails at), Gunn is best known for conveying human emotionality through non-human characters, such as Rocket Racoon and Groot. Krypto doesn’t quite reach the pathos of Rocket in the third Guardians of the Galaxy, nor the neoteny of Baby Groot in the second, but there’s a rambunctiousness to him which will be familiar and endearing to all dog lovers.

Rachel Brosnahan as Lois Lane almost certainly would have worked better in a period piece, as she was clearly cast for her role as the (truly) Marvelous Mrs. Maisel. Had she simply reprised that role under the new name Lois Lane, it would have worked better, but some confluence of script, wardrobe, direction, and other myriad factors were working against that proven formula. Her standout scene comes early in the film, in which she’s allowed to interview Superman for the first time. It’s one of the best portrayals of Lois Lane doing realistic journalism, as opposed to previous iterations in which she would always sneak into a criminal lair and immediately get captured. Such was obviously done to occasion her rescue by Superman, but always made her look incompetent at her job.

And yet the film is worse for disposing of the damsel in distress element of her dynamic with Superman altogether. Modern society is pathologically embarrassed by the notion of a woman ever needing a man, or depending on him – even a man who’s all-powerful and all-good, in the case of Superman. Thus we’re robbed of charming scenes like in the ‘78 film in which Christopher Reeve confidently assures Margot Kidder “Easy miss, I’ve got you”, followed by her very genuine reaction: “Who’s got you?!?” Instead, the Lois of the ‘25 film still places herself needlessly in harm’s way, not even as a display of her journalistic pursuit of truth, but rather in order to play at heroine herself.

Nor are her actions ethical or even rational. Instead of infiltrating a criminal enterprise or gang headquarters, she decides to break Superman out of lawful detainment to which he voluntarily surrendered himself. Gunn’s purpose for which seems first and foremost to perpetuate the ‘dude in distress’ trope that has become vogue in modern media, and secondly as a political statement in which all detention is illegitimate and all detainees are innocents.

As for Superman’s pal Jimmy Olsen, he is the subject of a repeating gag throughout the film which plays upon his comic counterpart’s inexplicable ability to date women closer to Superman’s league than his own. It’s hilarious cringe comedy when the plain-faced Skyler Gisondo is so visibly unenthusiastic about the prospects of having to endure an entire weekend with the gorgeous and fawning Eve Teschmacher, played by literal Victoria’s angel Sara Sampaio, who’s acting chops are proven everytime she looks at Jimmy with ‘crazy eyes’. And unique to live action portrayals it channels a modicum of the energy and excitement of Jimmy’s life as portrayed in comics like All-Star Superman.

The other denizens of Metropolis are likewise comics-accurate, and better for it. Making their film debuts are Cat Grant, Steve Lombard, and Ron Troupe. All are under utilized compared to their comics counterparts, where Cat contrasts a try-hard sexuality with Lois’ natural beauty; Lombard contrasts a blowhard bravado with Superman’s soft-spoken chivalry; and Troupe contrasts the kind of journalist Clark could be without the distraction of saving the city. In the film, Lombard is reduced to the same sketch comedy character that Beck Bennett played in every scene of Saturday Night Live, while Mikaela Hoover’s Cat simply serves as eye candy. But their inclusion is welcome nonetheless.

Rounding out the Daily Planet’s background bit parts is Perry White, in a much reduced role compared to previous iterations. But as with Laurence Fishboure as Perry in Man of Steel, Wendell Pierce is another example of race-swapping done right, with his anachronistic indoor cigar chomping helping to retain the spirit of the character.

Nicholas Hoult’s Lex Luthor is the bald-headed business mogul fans have always wanted to see onscreen, blending in also the criminal henchmen of the Hackman-era with the mad scientist elements of the character’s earliest portrayals. His standout scene is where he displays a surprising amount of self-awareness, openly admitting to being driven by envy, showing his emotional intelligence (though not wisdom or virtue) matches his super-genius intelligence in other matters. But such envy, alongside his racism-coded distrust of Superman as an alien (in the film loaded with the double meaning of extraterrestrial and foreigner), get the character of Lex Luther wrong, because they get the character of Superman wrong first, against which Lex is merely antithetical and antagonistic. While there was much to dislike about Snyder’s Superman films and Jesse Eisenberg’s portrayal of Luthor, the Dawn of Justice script got to the very heart of the conflict between the villain and hero by making Lex a misotheist driven by hatred of God.

All of which is preamble to the main critique of James Gunn’s Superman: James Gunn’s Superman.

There are two main schools of thought regarding Superman: one which emphasizes the “super”, and another which emphasizes the “man”. The latter has admittedly been expressed by many great writers of great Superman stories throughout the decades. Alan Moore ends “Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow?” with Jordan Elliot (née Kal-El) declaring “Superman? He was overrated and too wrapped up in himself. He thought the world couldn’t get along without him.” Mark Waid climaxes Kingdom Come with an admonishment from a Protestant pastor: “[Y]our instinctive knowledge of right and wrong. It was a gift of your own humanity… But the minute you made the super more important than the man… that took your judgement away.” Though Waid employs Christian imagery from the book of Revelation and draws deliberate parallels between Superman and Christ, it’s in deliberate rejection of the Christological motif.

Contra director Richard Donner, who’s Jor-El all but paraphrases the Gospel of John: “They can be a great people, Kal-El, they wish to be. They only lack the light to show the way. For this reason above all… I have sent them you, my only son.” A similar sentiment, put more poetically, is given by Jor-El in All-Star Superman and repeated verbatim in Snyder’s Man of Steel: “You will give the people of Earth an ideal to strive towards. They will race behind you, they will stumble, they will fall. But in time, they will join you in the Sun.”

In both these cases, and many others, we see Superman sent from the heavens by his father to be a savior and moral exemplar. His goodness is innate. It does not come from a quotidian Kansas upbringing. He has been gifted the Ring of Gyges, the Ring of Power even, and he alone can wield the power without succumbing to temptation to misuse it. Any ordinary Kansas farm boy would fail the test. And it is that understanding of Superman that makes the conceit of the secret identity make so much sense. Clark Kent is that same figure, sent from the heavens, but fully embodying all of our same human limitations, and yet still achieving the standard of moral perfection despite such. Clark, not Superman, is the “ideal to strive for”, the “light to show the way”.

So it’s telling that Gunn’s rendition of the Jor-El speech is a deliberate subversion of Donner’s and Snyder’s. Gunn’s Jor-El is not a heavenly father, instead sending his son to conquer Earth; and Gunn’s Superman is a hero for not doing the will of his father. This is further reflected in the character’s moral fallibility. In the climactic confrontation against Lex, Superman expresses the sentiment that he is just an ordinary guy doing the best that he can everyday, and screwing that up much of the time. This is the thesis of the film, hammered home in the final line of the post-credits scene, in which Superman surmises “I can be a real jerk sometimes.” It’s played for laughs, but at the expense of sacrificing everything unique about the character of Superman. Other heroes are ordinary men and women doing their best and not always knowing the right thing to do. But Superman is different. Superman is better.

Which makes Superman a difficult character to relate to, and therefore a (seemingly) difficult character to write stories about. Which is why the best Superman stories are not about him, but rather humanity’s need for him; our reactions to him; and our transformation by him.

But Gunn rather tries and fails to imbue pathos in the character of Superman through giving him moral uncertainty. The opening text of the film introduces the conflict of Superman having to choose between, on the one hand, saving innocent lives through unilateral action in foreign affairs, or, on the other hand, humbling himself to follow the same rules to which ordinary humans are subjected. This in itself is an interesting dilemma for a Superman story, but Gunn fails in two scenes in particular.

The first is Superman’s interview with Lois Lane. Beyond merely making him a hothead who uses his powers brashly without forethought, it reduces his entire ethical system to “people dying is bad”. While comic books have often oversimplified moral conflicts and ethical dilemmas in order to present clear heroes and villains, even within the logic of Gunn’s world this is acknowledged as gross oversimplification, as Lois points out in direct response, for which Superman has no answer but to fly off in frustration, having been defeated not by kryptonite, but by calm, rational discussion.

The second scene is the film’s climax, in which Boravia once again intends to invade Jarhanpur. In a well-told story, this should offer a resolution to the dilemma established earlier, with Superman showing moral clarity as to why or why not his intervention would be warranted. Instead, the script allows him to sidestep answering the question altogether, with the Justice Gang (the less said about whom the better) intervening in the conflict instead. The result is that the new status quo, in which metahumans unilaterally intervene in international affairs, is not driven by the actions or choices of the film’s purported protagonist.

Though Gunn surely thinks he’s saying something profound about conflicts such as Russia’s predations against Ukraine, or Israel’s anti-terrorism actions against Hamas, the conflict between Boravia and Jarhanpur is too broadly painted in order for any real world parallels to be drawn. The same could be said about Superman’s status as an immigrant. Whereas Man of Steel offered an extended metaphor in which the Old World was lacking in freedom, in which (through the genetic matrix) Kal-El was the embodiment of his people, in which he fully assimilated, proudly declaring to the general that he’s an American from Kansas, and in which he sides with his adopted homeland instead of his heritage, Gunn lacks a similar profundity. The closest he gets is an incoherent critique of Immigrations and Customs Enforcement during a scene in which Superman is declared to have no Rights on account of being an alien.

Slightly more explored – relative to runtime, though not in terms of depth – is the natural apprehension that Superman could be the vanguard for an alien invasion. Immediately upon Luthor’s leak of Jor-El’s message, the public turns against Superman with the fickleness of Roman plebeians at Caesar’s funeral. They then just as quickly they come back around to loving him during a particularly suspension-of-disbelief suspending scene, in which the headline story of an extra-dimensional rift actively ripping apart Metropolis gets pushed to chyrons in favor of reporting on the first initial allegations of Luthor’s machinations – the equivalent of reporting on an Epstien client list while planes that very moment were flying into the sides of skyscrapers.

Perhaps the most unbelievable moment of the film comes immediately after, when Maxwell Lord, played by Sean Gunn, proclaims that hating Luthor is the one thing conservatives and liberals could agree upon. Whether it’s their opinions of Luthor or Superman, if one side supported one and opposed the other, the other party would reflexively hate the former and love the latter. And vice versa. Our politics are too polarized to agree as to what is a woman, let alone who is the superman.

And that, fundamentally, is the question that the film fails to answer: who is the Superman? Jimmy Gunn might claim to be his pal, but he doesn’t know the Last Son of Krypton from Adam.